The Possibility of an Exhaustive Gift List

Is an exhaustive gift list even possible? Many have attempted to create a complete list of gifts, but others dispute whether this is advisable

[1] or even possible. Peter Wagner presents the prevailing view when he writes “none of the lists is complete in itself...And one could surmise that if none of the three lists is complete in itself, probably the three lists together are not complete

[2].” Coming from the opposite point of view, Bruce Black responds “If Wagner’s view of an open-ended list is correct, everything anyone does in the area of Christian service could be classified as the exercise of a spiritual gift

[3].” William McRae comes to the same conclusion through different reasoning.

Does the New Testament contain a complete list of the spiritual gifts given to the church? This is not easy to answer. It may be answered by asking, What possible gift would be added to the list? Upon reflection, the list is surprisingly complete. Eliminating natural talents, I cannot imagine a spiritual gift which could make the list more complete.[4]

Leslie Flynn takes an intermediate perspective on the gift lists.

One widely held view is that every possible gift for the church could be classified under one of the gifts in Paul’s three tabulations. Thus, though all the gifts in the church are not actually specified in Scripture, yet every unnamed, genuine gift could be subsumed under one of the listed gifts.[5]

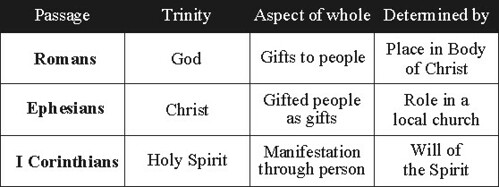

It is likely that Paul never intended to give us a “master list,” given the partial nature of the lists he did leave; but it is not a conclusive argument given that many doctrines are pieced together from different biblical authors. Whether Paul meant to leave us with an exhaustive gift list is not the same question as “Did the Holy Spirit mean to leave us with a complete list?” It is at least possible that He did.

Building the List

The purpose of a gift list for this research is practical. A correct list will help the church identify which gifts we should look for in ourselves and others, and it will also determine how the gift-type theory stands against a normal (in this case literal) reading of the relevant bible passages. But the material we have to work with is difficult to put together into a comprehensive picture. So how do we construct a list of gifts from the bible as a guide for what to look for? A literal hermeneutic will be used here. Letting the text speak for itself is the only objective criterion we have and involves only two guidelines: Do not add to or subtract from what is written.

Principle 1: Do not add gifts to the list (A.) Some gifts are added by suggestion. A bible passage might imply the existence of another gift not mentioned in the major gift passages.

(B.) Some gifts are added by intuition. The writer believes he/she has seen a gift in action that is not listed in the bible.

Principle 2: Do not subtract gifts from the list(A.) Gifts are sometimes edited out of consideration by combining them with other gifts, e.g. leadership and administration are often combined into the gift of ruling. A strict interpretation will view distinct Greek words as having distinct meanings, and unless the text suggests otherwise each gift should be considered separately.

(B.) Gifts can be taken out of consideration when they are unnecessarily defined as supernatural and therefore limited to the early Church.

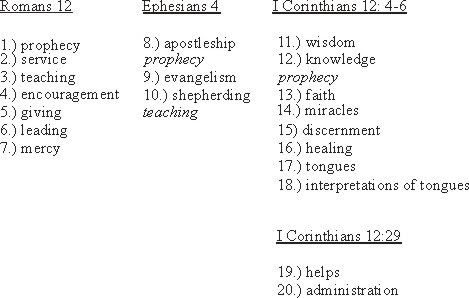

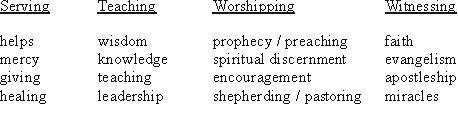

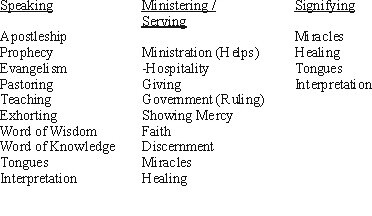

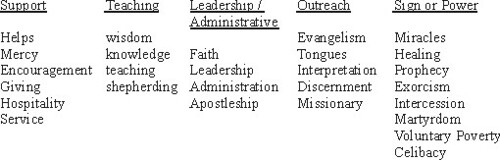

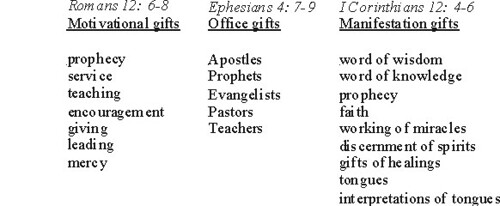

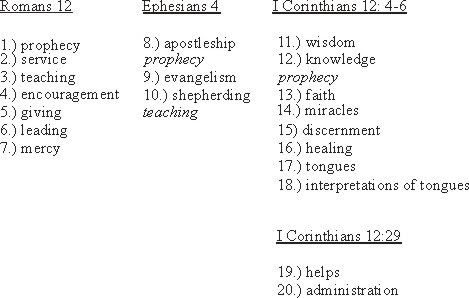

A Starting Point: Paul’s Gift ListsThe following lists provide our raw material. Any repeated gifts are in italics.

A literal reading of these lists yields the 20 unique gifts numbered above.

Gifts to Remove From the ListApostleship Apostleship is viewed by many to have involved a set of circumstances peculiar to the early church

[6], such as having seen the risen Christ

[7]. Some extend the gift to include modern church planters

[8]. The place of apostleship has been elaborated at length in books and articles. If we take the majority opinion and subtract apostleship from our list we have 19 gifts remaining.

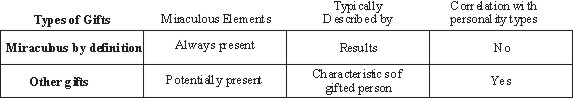

Miraculous GiftsSeparating the supernatural gifts by applying the categorical distinction of “miraculous by definition” removes four more gifts from the list: Miracles, healing, tongues, and interpretation of tongues. These gifts are detectable only by the results of using them and not by personality factors. We now have 15 gifts.

Gifts to Consider Adding to the ListVoluntary poverty and Martyrdom. The primary source for these additional gifts is Bridge and Phypers. They find two extra gifts in I Cor. 13:3 Voluntary poverty

[9] and Martyrdom

[10]. The wording in verse 3 is ambiguous and the designation as gifts must be inferred from the context.

“And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, but have not love, it profits me nothing.” (I Cor 13:3, NKJV)

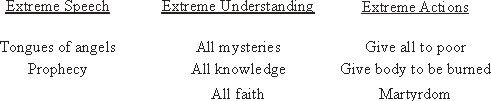

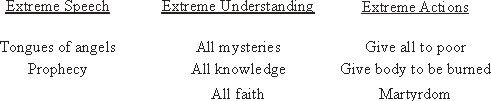

Although the overall context is the charismata, Paul is deliberately using extreme language. The structure of I Corinthians 13 must be examined to understand the relationship of voluntary poverty and martyrdom to the gifts. In verses one to three Paul gives us a list of good things taken to extreme. The general categories would be as follows:

All of these qualities but the last one, martyrdom, correlate with a gift, “understanding all mysteries” being a likely reference to the gift of wisdom

[11](I Cor. 2:7). The use of gifts to derive these qualities is intentional to make a point. Taking “all knowledge” as an example, here is the logical relationship: If I go beyond the gift of knowledge to “all knowledge” it is still worthless without love, how much more is just the “gift of knowledge” worthless without love.

The logical progression is

So the hypothesized gift of voluntary poverty is just the gift of giving in absolute form. It is then no different from “all knowledge” and “all faith,” which are not gifts, but gifts hyperbolized

[12] to give perspective to love. And martyrdom is just the final step beyond any of the gifts. Even this most self-sacrificing act can only have meaning when done in love.

Celibacy I Corinthians 7:7. Celibacy has the best case for consideration as an additional gift. If so it would be an exceptional and rare gift and would not correlate with any psychological types.

Exorcism Exorcism

[13] is equated by some with the gift of miracles (powers), but it is never stated as a gift and must be inferred as one.

Intercession Wagner includes intercession because he has “seen it in action

[14],” otherwise it has very little evidence supporting gift status.

Craftsmanship Found in Bridge and Phypers (1973) reference to Exodus 31:3, which is clearly speaking of a person gifted by God "in every kind of craft," but not in the sense of the charismata. God has arranged for this ability by giving excellent craftsmanship skills to other gifts such as faith and service. People with extraordinary skill in craftsmanship are clearly gifted, but there is scant evidence to include craftsmanship among the charismata.

Music Used through other gifts but nowhere mentioned as a charisma.

HospitalityHospitality, the 16th gift necessary for the gift-type theory, is found in I Peter 4:9. This gift is often found in gift lists, but there are some authorities who do not include it. Bruce Black notes that Peter’s exhortation to “Be hospitable” was directed to all Christians

[15]. Black believes that hospitality can, however, be a vehicle for the gifts of serving and giving

[16]. McRae suggests that it “may be one of the outlets for the gifts of helps or mercy

[17].” Including hospitality in our list does violate the strict rules of constructing a gift list cited above, but there are three possible reasons to consider adding it.

1. The proximity to the exhortation to use our gift earns it consideration as a separate gift. As Leslie Flynn reasons,

Though hospitality is not included in any of Paul’s lists of gifts, the context in which hospitality is mentioned seems to earn it consideration as a separate gift. After Peter speaks of hospitality in verse 9, he immediately goes on in the next two verses to say that whatever gift a person has should be faithfully exercised. The link in Peter’s thinking between hospitality and gifts strongly implies that hospitality is a gift.[18]

2. We can see it in action. By itself, this is a weak argument as there are many abilities we might claim to see.

3. It completes the picture. There are fifteen gifts which line up with fifteen psychological types. The type left over just happens to be the type described as “Hosts and hostesses of the world

[19]”. Ultimately, however, the biblical texts should be our determining factor, and the reader can decide if Peter’s wording is sufficient reason to include hospitality in our list.

Be hospitable to one another without grumbling. As each one has received a gift, minister it to one another, as good stewards of the manifold grace of God. (I Peter 4:9-10)

If we count hospitality as a separate gift, we have the 16th gift in the gift-type theory, but the issue of synonymous gifts must be considered first, before we confirm the list.

Combined gifts Gifts that sound similar are often combined as if they were synonyms. These pairings of gifts are nearly always based on an intuitive response of the author and not on any analysis of the Greek, and only rarely on the respective functions of the gifts.

Leadership and Administration The gift of ruling is often postulated as the combined function of leadership and administration. The Greek terms, though, of kubernesis (administration) and prohistami (leadership) are clearly distinct words with distinct meanings. The leader (one who stands before) is clearly distinct from the administrator (steersman of a ship). The leader must choose the destination, but the steersman’s destination is already known, and the job is to reach the destination.

Helps The gift of helps is the most frequent target for blending with another gift. At least four other gifts have been combined with helps by different authors.

1. Service: The helps-service combination is the most common and is sometimes called the gift of ministry.

2. Mercy: Billy Graham is one source for the helps-mercy combination. “Helps is the gift of showing mercy[20].”

3. Giving: Robert L. Thomas places giving as “a specialized form of the gift of helps[21].”

4. Hospitality: Mels Carbonell writes that “some of the many gifts in scripture are similar to others, such as, the gifts of helps, hospitality, and serving. They are described in similar terms. To avoid redundancy and complexity, we’re going to combine these into one: ‘ministry / serving[22].”

The variety of combinations for the gift of helps show the subjective, even arbitrary, nature of combining separately listed gifts into one. The only other combination left to consider is that of pastor and teacher. These gifts from Eph. 4:11 are sometimes combined into the gift of pastor-teacher based on the Greek construction. Much of the recent scholarly analysis of this verse has concluded that the two gifts should not be combined. The analysis, however, is fairly technical and is saved for appendix B.

Summary and Conclusion A gift-type theory of spiritual gifts is compatible with a normal reading of scripture, with the possible exception that the gift of hospitality is not stated explicitly as a gift and must be inferred from the context. Otherwise, the theory is supported by the most literal reading possible of the relevant passages. The following is a summary of the above analysis.

A literal reading of Paul’s Gift Lists Total = 20Subtract Apostleship Total = 19Subtract the miraculous gifts of Miracles, Healing, Tongues, and Interpretation Total = 15Consider additional gifts / only add hospitality from I Peter 4:9-10 Total = 16Avoid arbitrarily combining gifts Total still = 16References[

1] Stone, citing Higgs p. 45, Lists as Literary Devices, suggests that the lists are only samples, and that the attempt to use them to identify our own gifts may be a pointless and frustrating endeavor. p. 23, Relationship Between Personality and Spiritual Gifts. Psy.D Diss., (George Fox College: University Microfilms International, 1991). The gift-type theory depends on a literal-normal hermeneutic, contra Stone and Higgs.

[

2] Peter Wagner, Your Spiritual Gifts can Help Your Church Grow (Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 1979), 62; echoed by Carson, D. A., Showing the Spirit: A Theological Exposition of 1 Corinthians 12-14 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1987), 35.

[

3] Black, Bruce W., The Spiritual Gifts Handbook: The Complete Guide to Discovering and Using Your Spiritual Gifts (Neptune, NJ: Loizeaux Brothers, 1995), 32.

[

4] William McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1976), 81.

[

5] Leslie Flynn, 19 Gifts of the Spirit (Wheaton, IL: Victor, 1994), 37.

[

6] Thomas, Robert L. Understanding Spiritual Gifts: A Verse-by-Verse Study of I Corinthians 12-14. Rev. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1999), 174–176.

[

7] Jack Deere speculates that Paul’s method of seeing the risen Christ in a vision could be repeatable today,

Surprised by the Power of the Spirit (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1993), 248. although he also argues that apostleship is a God-given commission and not a spiritual gift, p.242; see also C. Samuel Storms, in response to Robert L. Saucy and Richard P. Gaffin, who points out that “the term charisma is never applied to apostleship;” also “Exhorters exhort, teachers teach, healers heal…But how does an “apostle” (noun) “apostle” (verb)? Whereas both Saucy and Gaffin insist that apostleship is a spiritual gift, neither one defines it.” Wayne Grudem, ed., Are Miraculous Gifts For Today?: Four Views (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 156.

[

8] Kenneth Kinghorn, Gifts of the Spirit (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1976), 43–47; also Gangel, Unwrap Your Spiritual Gifts (Wheaton, IL: Victor, 1983), who separates the gift from the office p. 26–27.

[

9] Voluntary poverty has been considered a gift as far back as St. Cyril of Jerusalem in the Fourth Century, Lecture XVI.

[

10] The gifts of celibacy and martyrdom make possibly their first appearance (with the exception of St. Cyril in the reference above) in 1973 with the first edition of Spiritual Gifts and the Church by Donald Bridge and David Phypers (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1974), 25; although the gifts have become much better known through Peter Wagner since 1979.

[

11] Cf. Robert L. Thomas, Understanding Spiritual Gifts: A verse-by-verse Study of I Corinthians 12-14 (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1999), 69, 211.

[

12] Cf. Wayne Grudem, The Gift of Prophecy in the New Testament and Today (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2000), 102.

[

13] There may be an attraction of the ESTP evangelist to excorcism where they can use their instinct for knowing how much of God’s power can be claimed in a given situation.

[

14] 1979, p.74.

[

15] Black, 93.

[

16] Ibid, 94.

[

17] McRae, 80.

[

18] Leslie Flynn, 19 Gifts of the Spirit (Wheaton, Il.: Victor Books, 1994), 122.

[

19] Otto Kroeger and Janet M. Thuesen, Type Talk (New York: Broadman Press, 1988), back cover.

[

20] Billy Graham, The Holy Spirit (Warner Books: New York, 1980), 76.

[

21] Thomas, 202.

[

22] Carbonell, 162.

powered by performancing firefox